In 1988, as the Reverend Jesse Jackson was making his second presidential bid, I left the campaign trail, where I was covering the eventual Democratic nominee, Michael Dukakis, to make a personal pilgrimage to Wichita, Kansas. I had come to see my sick grandfather, Ga-Ga, who was comatose in the hospital and seemed barely there.

Day and night, I held his hand hoping he would make it. I knew he had admired Jackson’s first presidential bid in 1984 and the courage—some called it audacity—required to run at all. So I told him about the huge, overwhelmingly white crowds Jackson was drawing in places like Iowa and Wisconsin. There was a refrain Jackson had been using in Iowa to convince audiences he really could win this time: “Great days just keep on coming.” I was not sure if Ga-Ga could hear me, but I repeated the refrain to him, trying anything I could to uplift him as he struggled to hold on to his life. “Great days just keep on coming.” And to my surprise, I glimpsed a thin smile, and he squeezed my hand.

Ga-Ga didn’t make it. But Jackson came much closer to winning the Democratic nomination than anyone had expected. He won 11 primaries and caucuses, doubled his 1984 combined-vote total to nearly 7 million, and finished as runner-up to Dukakis. His impact in that hospital room—and he wasn’t even there—eliciting a glimmer of life from my dying grandfather, has always stayed with me.

For many years, I watched firsthand how Jackson stirred to joy those “who catch the early bus” to work, as Jackson liked to say—cooks, janitors, housekeepers, construction workers, tenants in housing projects.

We see little of this gift now, the ability to project hope in a fractured country, to instill belief in those who’ve lost it. Our politics has become coarse and tawdry, and the highest levels of elected office seem no place to turn to for inspiration. Who can be counted on to convert gloom into optimism with a speech?

[Adam Serwer: Do not be cynical about Jesse Jackson]

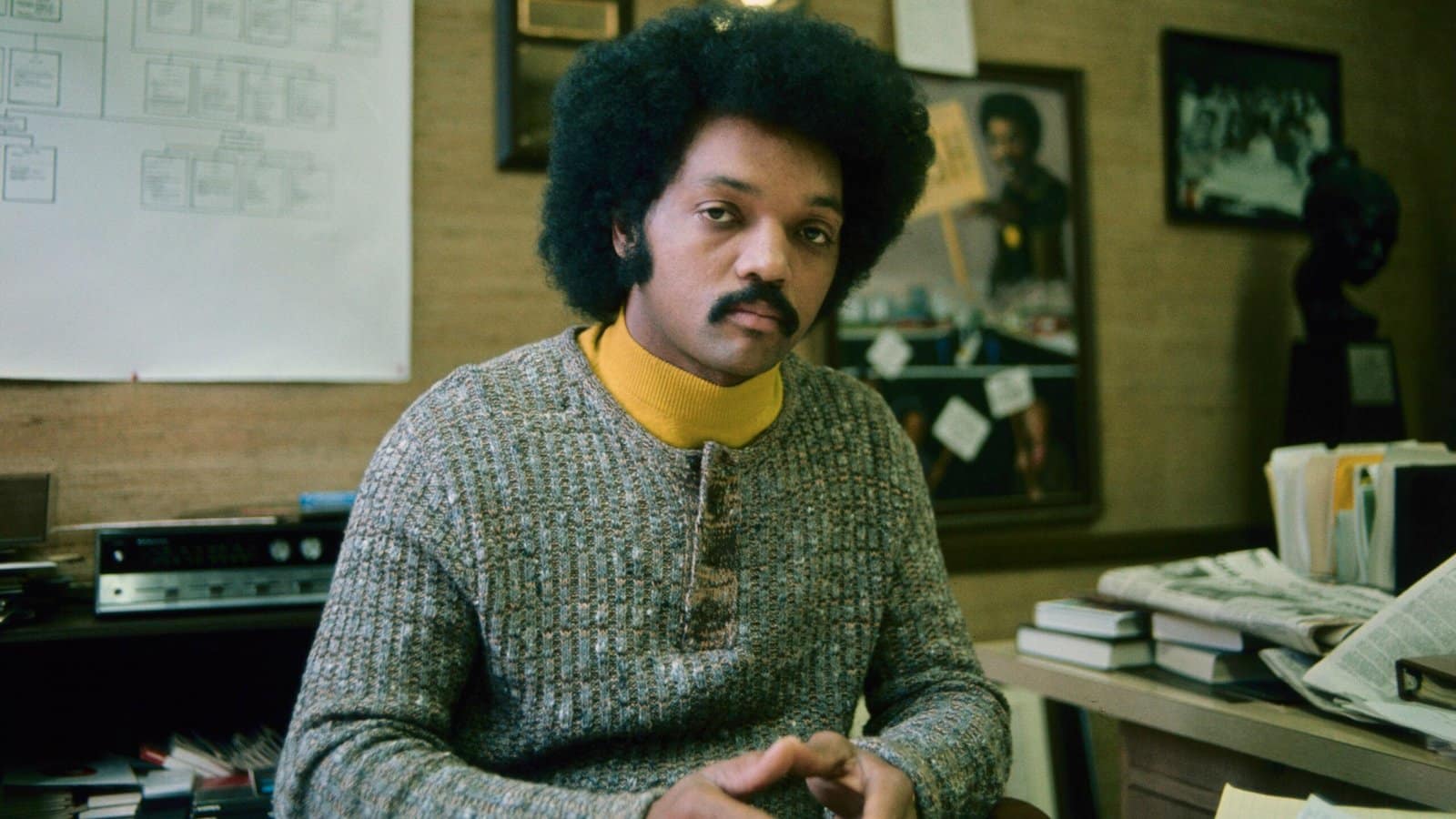

Jesse Louis Jackson, who died Tuesday at 84, was one of the most consequential political figures of the 20th century and among the greatest orators America has ever seen. This goes well beyond his credentials as a civil-rights leader who participated in the sit-ins and marches of the 1960s. He was brilliant, voracious, provocative, and persuasive all at once, at times electrifying and at times confounding.

I interacted with Jackson, on and off, for 30 years—on private planes and in late-night phone calls, at diners and Black churches. I once watched Jackson dash to officiate a wedding for a friend between campaign stops.

Black political leaders of varying significance had been discussing running for president ever since Shirley Chisholm’s inspiring campaign in 1972, which became a feminist cause to rally around. Those conversations intensified after Harold Washington’s 1983 victory to become Chicago’s first Black mayor. But none of the likely Black politicians—including, notably, then–Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young—took the leap. Most thought it was a symbolic fool’s errand that at best would end in crushing defeat and at worst would damage relationships inside the Democratic Party. Only Jackson had the daring to go for it, urged on during a national voter-registration drive in 1983 by large crowds of supporters who’d chant: “Run, Jesse, run!”

Perhaps the most significant part of Jackson’s electoral success in 1984 and 1988 was how his campaigns opened up the Democratic Party to an influx of new field-workers, operatives, and volunteers, many of whom had never before participated in electoral politics. Jackson also pushed through a crucial change in party rules that later benefited Barack Obama’s historic candidacy in 2008. Because of Jackson, delegates in Democratic primaries and caucuses are now awarded proportionally according to the results in each state. Previously, some states used a winner-takes-all system. Twenty years later, Obama was able to build an insurmountable lead over his closest rival, Hillary Clinton. He continued to rack up delegates despite her winning nine of the last 16 contests. To say that the first Black president owes a lot to Jesse Jackson is an understatement.

Jackson’s mind was not like others’. He used to say, “If you need an alarm clock to wake up, you’re already behind.” How he managed to do so much, to keep such a vigorous schedule, which would often shift abruptly, was a marvel. I was in the middle of interviewing him once on his private jet headed to Iowa. He paused and said: “Buddy, I’m gonna close my eyes for about 20 minutes. I’ll get right back to you.” It was like he was taking a commercial break from the interview.

And sure enough, after 20 minutes of shut-eye, he awoke and resumed the interview like he had never left it.

His uncommon ability to create metaphor and imagery left audiences repeating lines and catchphrases, as though he were Kendrick Lamar on tour. “We who are giants must stop having grasshopper complexes and grasshopper dreams,” Jackson said during an Atlanta breakfast I attended in 2000. “We are not grasshoppers.”

I used to think Jackson was naturally blessed with the talent of combining words, that retention of complex ideas and cadence of delivery were just his superpowers. But I learned that he had a process, like athletes have—a pregame ritual. “I get up early and study,” Jackson told me. Sometimes before dawn. “To do what I do does require preparation. That must be the most underrated part of this work. If you ain’t on fire, you can’t give off heat.”

“The only way you can speak with authority,” he added, “is if you have command of your material.”

Having command of his material served Jackson well, except when it didn’t—when he hadn’t worked out all of the details and couldn’t answer all of the questions.

Peripatetic isn’t a big-enough word for Jackson’s rolling set of interests: school-board disputes, wars, poverty, voting rights, hostage negotiations, Wall Street, Silicon Valley. Nothing seemed to be off his plate, and thus there sometimes seemed to be too much on his plate. The chance to build a large movement, perhaps even a viable third party, seemed squandered. His promising multiracial National Rainbow Coalition, including farmers, laborers, youth, women’s-rights activists, never got organized into a true progressive electoral force. Sustained focus and infrastructure were not Jackson’s strengths.

Anyone who happened to be on Jackson’s radar—and the focus of that radar changed from year to year, sometimes from month to month—knew to expect a call from him at any time. He knew whom to call for what, whom to enlist and how to enlist them.

Bill Daley, who was the chairperson of Al Gore’s 2000 campaign, marveled at the pace Jackson kept. “The only problem,” he told me during that run, was that “he stays up too late. He calls in the middle of the night. Fortunately, I learned I had an ‘Off’ button on my cellphone. Though when I turn it back on in the morning, the first message is usually from Reverend Jackson.”

Long before everyone had cellphones, Jackson would call me at home on my landline, typically at 10 or 11 p.m., sometimes midnight. These calls would be more like soliloquies than conversations. Jackson would do all the talking, letting me know about a particular injustice he was concerned about, briefing me on an issue campaign he was about to embark on, or railing about something in the news he thought was not right or fair. He would dish, but also educate.

[Clint Smith: Those who try to erase history will fail]

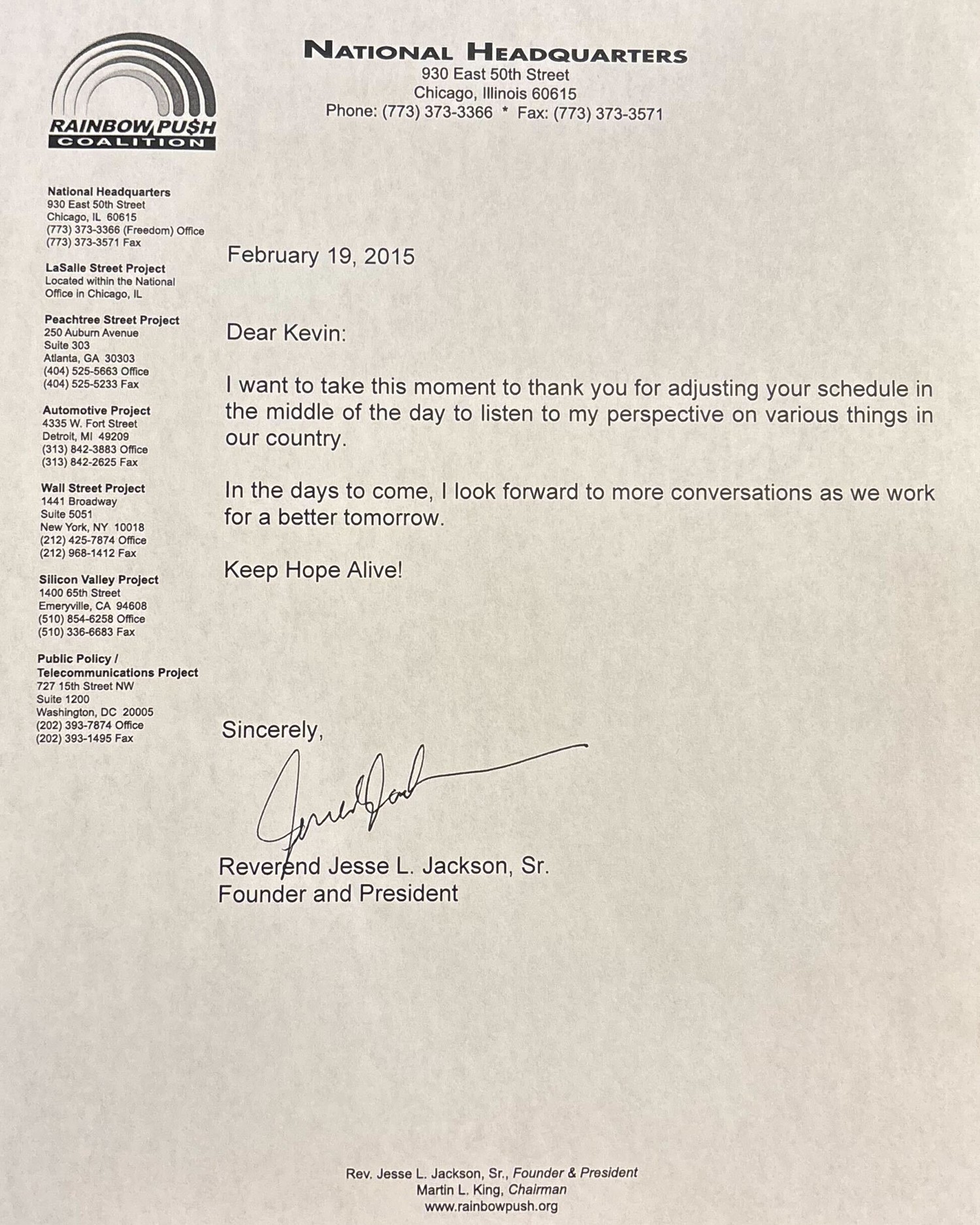

One day in February 2015, Jackson showed up in the lobby of The Washington Post and asked to speak with the managing editor. At the time I was one of two managing editors, and the first African American to hold the position in the Post’s history. The call from the security desk came to my assistant, who seemed shocked that the Jesse Jackson was downstairs in the lobby unannounced. I was not shocked; I had seen Jackson just show up to places many times, just as he made calls without giving notice.

Though I was busy at the time, I rearranged my schedule, and Jackson was escorted up. He had two or three aides with him. I don’t remember exactly what his business was that day—some new cause he was advancing. He seemed pleasantly surprised, and full of pride, that I had a big office and was overseeing daily coverage in the newsroom. We talked for about 20 minutes, and then I ushered him to the elevators and thanked him for dropping by.

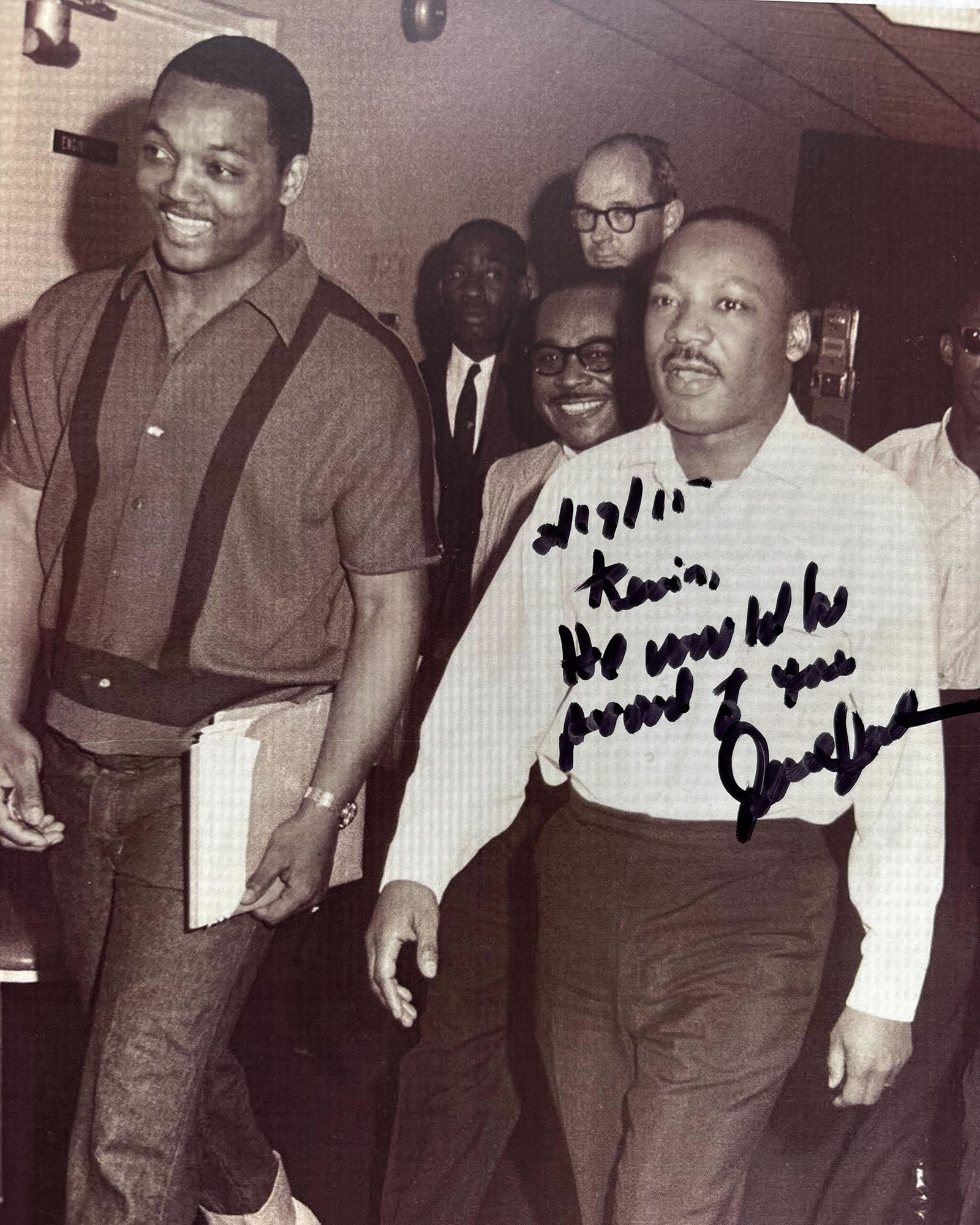

About a week or so later, I got a package in the mail. It was a photo of Jackson and Martin Luther King Jr. during their young civil-rights-activism days. It was signed by Jackson with the inscription, “He would be proud of you.”

The photo, and an accompanying letter thanking me for adjusting my schedule, caught me off guard. I had never seen Jackson do anything like that.

The notion that King would be proud of me? That brought me to tears. I stared at the picture for a while. It was a reminder of how hard King, Jackson, and many others who are now gone worked to open the doors of opportunity throughout this country—including in newsrooms, where those doors had long been shut to people like me.