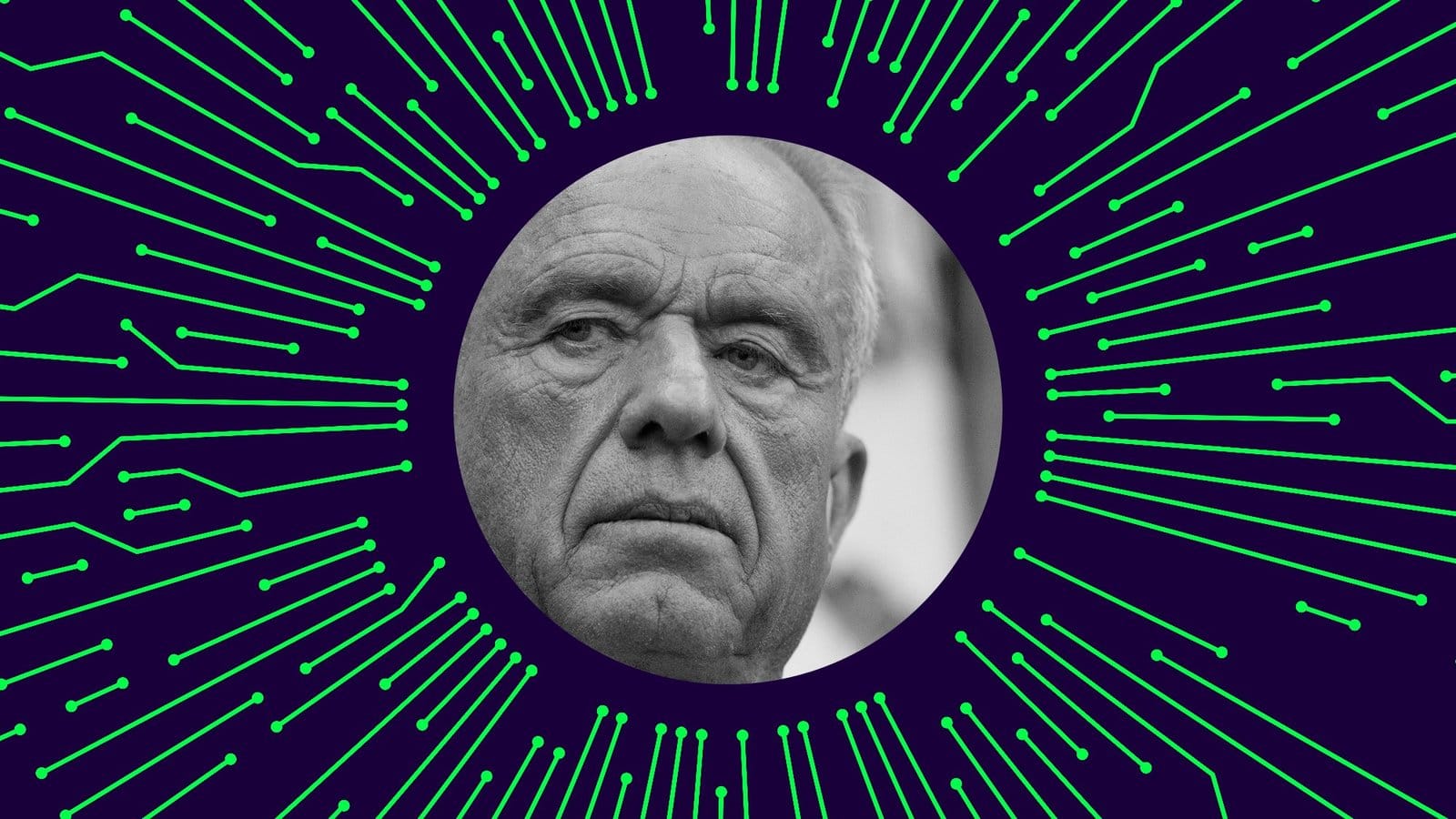

Robert F. Kennedy Jr. is an AI guy. Last week, during a stop in Nashville on his Take Back Your Health tour, the Health and Human Services secretary brought up the technology between condemning ultra-processed foods and urging Americans to eat protein. “My agency is now leading the federal government in driving AI into all of our activities,” he declared. An army of bots, Kennedy said, will transform medicine, eliminate fraud, and put a virtual doctor in everyone’s pocket.

RFK Jr. has talked up the promise of infusing his department with AI for months. “The AI revolution has arrived,” he told Congress in May. The next month, the FDA launched Elsa, a custom AI tool designed to expedite drug reviews and assist with agency work. In December, HHS issued an “AI Strategy” outlining how it intends to use the technology to modernize the department, aid scientific research, and advance Kennedy’s Make America Healthy Again campaign. One CDC staffer showed us a recent email sent to all agency employees encouraging them to start experimenting with tools such as ChatGPT, Gemini, and Claude. (We agreed to withhold the names of several HHS officials we spoke with for this story so they could talk freely without fear of professional repercussions.)

But the full extent to which the federal health agencies are going all in on AI is only now becoming clear. Late last month, HHS published an inventory of roughly 400 ways in which it is using the technology. At face value, the applications do not seem to amount to an “AI revolution.” The agency is turning to or developing chatbots to generate social-media posts, redact public-records requests, and write “justifications for personnel actions.” One usage of the technology that the agency points to is simply “AI in Slack,” a reference to the workplace-communication platform. A chatbot on RealFood.gov, the new government website that lays out Kennedy’s vision of the American diet, promises “real answers about real food” but just opens up xAI’s chatbot, Grok, in a new window. Many applications seem, frankly, mundane: managing electronic-health records, reviewing grants, summarizing swathes of scientific literature, pulling insights from messy data. There are multiple IT-support bots and AI search tools.

The number of back-office applications suggest the agency may be turning to AI in an attempt to compensate for the many thousands of HHS staff who have been fired or taken a voluntary buyout over the past year: For example, the database points to a “staffing shortage” as the reason why the agency’s Office of Civil Rights is piloting ChatGPT to identify patterns in court rulings involving Medicaid.

There are many ways this might go wrong. AI tools continue to make unpredictable errors; it’s very easy to imagine a tool intended to eliminate “fraud” accidentally cutting off someone’s Medicaid, or a tool intended to help ICU physicians recommending the wrong medication or dosage. In May, the agency released its landmark Make Our Children Healthy Again Report, which suggested that the government use AI to analyze trends in chronic-disease rates, including that of autism. The report was riddled with fake citations that appeared to be hallucinated by AI, which the White House attributed to formatting errors; HHS then corrected the report by removing the false citations and swapping in new references.

[Read: The two sides of America’s health secretary]

Several HHS employees told us that new AI tools in the department indeed make frequent errors and do not always fit into existing workflows. Despite the big claims that the administration has made about Elsa, the chatbot is “quite bad and fails at half the tasks you ask it for,” a FDA employee told us. In one instance, the staffer asked Elsa to look up the meaning of a three-digit product code in the FDA’s public database. The chatbot spit out the wrong answer. According to the same staffer, an internal website highlighting potential uses of Elsa includes relatively run-of-the-mill tasks such as creating data visualizations and summarizing emails, but because of hallucinations, “most people would rather just read the document themselves.” Another official said that he tried to use Elsa to evaluate a food-safety report. “It processed for a moment and then said ‘yeah, all good,’ when I knew it wasn’t,” the employee told us.

Some staffers we spoke with did have a more positive take. One CDC official said that his team is “constantly reporting on efficiencies that they are gaining using AI,” even if those use cases are routine, like summarizing documents. Many of the tools HHS is using seem well intentioned. A tool used by federal and local health departments, for example, allows officials to analyze grocery-store receipts gathered from people suffering from suspected foodborne illnesses around the country to search for commonalities in the foods they ate. In an email, Andrew Nixon, an HHS spokesperson, told us that “a small number of disgruntled employees” have had problems with the agency’s AI tools. Many staffers, he said, “report that it improves their efficiency in carrying out their work.” Nixon added that even with staff shortages, the agency is “fully equipped to fulfill its duties.”

If anything, Kennedy is following the kinds of automations that are already being applied across health care. Medicine has become one of the biggest sources of hype for AI, with many ongoing attempts to both streamline the convoluted world of health care and produce life-saving research. Just as one example: Doctors can spend more than a third of their days writing notes, reviewing charts, and working through insurance claims in electronic-health-records systems. If AI products can automate just a bit of that work, health-care workers—which the U.S. has a chronic shortage of—will have more time to spend with patients. HHS is piloting AI tools that can streamline health records, as are many hospital networks around the country. Start-ups are working on building all sorts of AI health tools; both OpenAI and Anthropic recently launched health-care products.

The greatest promises of AI for health care are much flashier: curing cancer, discovering novel vaccines, treating previously incurable conditions. And there are, in the department’s approach to AI, some signs of an emerging technological paradigm shift. The HHS AI inventory reports a number of more ambitious projects, including using the technology to more quickly identify drug-safety concerns and study the genome of malaria parasites. These are AI tools that could genuinely change the kind of work doctors, epidemiologists, and medical researchers can do. AlphaFold—a protein-folding algorithm whose creators at Google DeepMind recently won a Nobel prize—is now used by researchers worldwide to advance drug discovery, including those at HHS.

[Read: A virtual cell is a ‘holy grail’ of science. It’s getting closer.]

Still, generative AI is not going to instantly supercharge the inner workings of HHS. (Even something as proven as AlphaFold only accelerates one slice of a very long drug-discovery process.) This is probably a good thing—the technology has come a long way, but also isn’t ready to totally remake one of the most influential public-health bodies in the world. If HHS continues to stick with an incremental approach to AI adoption, it could yield substantial improvements that are simply invisible to most.

But RFK Jr. may not be interested in stopping there. Many use cases are still being deployed or piloted, and the agency’s AI database is filled with jargon and platitudes that, in many instances, can be interpreted in multiple ways. When the administration says AI is or could be used for “Reviewing Global Influenza Vaccine Literature” or analyzing data in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, the end results could be innocuous—or not. When Kennedy talks about using AI to eliminate fraud, he might mean using the technology to fire another 10,000 employees crucial to the nation’s public-health infrastructure. The inventory outlines means rather than motivations. In at least one listed use case, though, the design is openly political: HHS is deploying AI to identify positions in violation of President Trump’s executive orders on “Ending Radical and Wasteful Government DEI Programs” and “Defending Women From Gender Ideology Extremism.”

Generative AI is undoubtedly a tool for bureaucratic efficiency and scientific research. But the more pressing question than what the technology is capable of is what ends it will be used to achieve.