This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

Americans don’t always know where their tax dollars are going, nor do they always agree with how they’re used. President Trump has an unorthodox proposal for where 10 billion of them should go: directly to him.

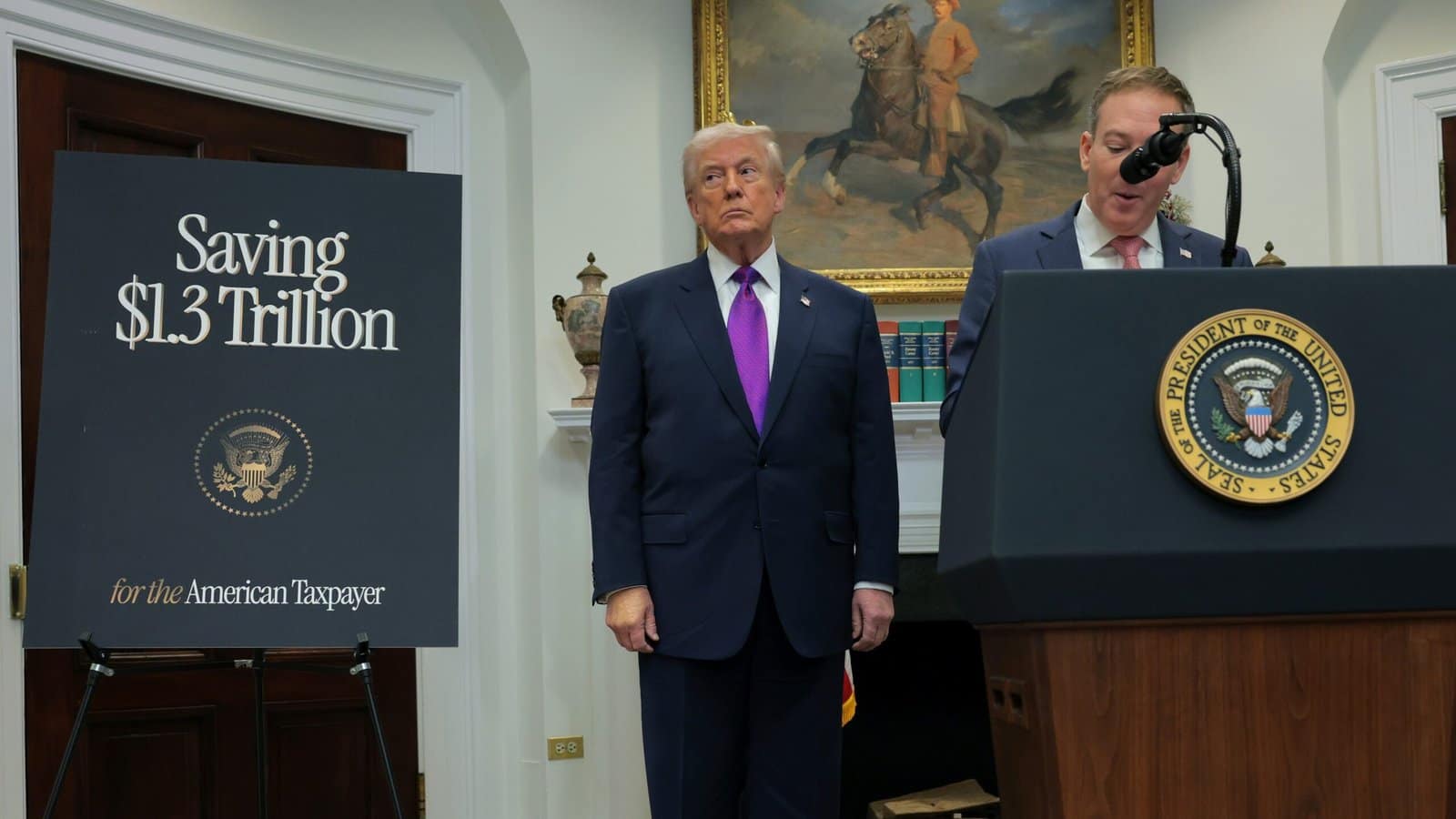

On January 29, Trump, along with the Trump Organization and his sons Don Jr. and Eric, sued the IRS for mishandling his tax information. The group is claiming improper disclosure—that a contractor leaked the president’s and his sons’ tax returns to The New York Times and ProPublica during Trump’s first term. (As part of his 2023 guilty plea for disclosing tax-return information without authorization, the contractor admitted to leaking Trump’s information to the Times.) The president is seeking $10 billion in damages; Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent confirmed last week that all of it would come from the Treasury General Account, which consists entirely of taxpayer dollars.

The suit taps into a real issue: Taxation doesn’t work without privacy. In order to fully comply with the system, Americans need to be able to trust that their personal details won’t be made public. Anyone can pursue legal action after getting their data leaked; the tax code specifically allows for it. But Trump, who is suing the IRS in a personal capacity, also happens to be the president, which means that his job involves overseeing the agency and its parent, the Treasury Department. This circulation of taxpayer dollars to the president’s personal bank accounts by way of litigation would be the first such transfer in U.S. history, experts told me. (Trump also made history when he refused to release his returns despite having previously pledged to do so, thereby breaking the modern tradition of presidents voluntarily showing the American people their tax information.)

The lawsuit itself raises a few big questions. An amicus brief, co-filed by two watchdog organizations and four former government officials, argues that the case could be thrown out because Trump actually missed the date by which he was supposed to file. And the fact that the leaker was a contractor of the IRS at the time of the leaks, not an employee, could potentially get the case tossed on its own.

Then there’s the question of the $10 billion—an obscene amount on its face, but not entirely without logic. The tax code allows plaintiffs to sue for $1,000 per each instance of disclosure, or for an unspecified amount of “actual damages.” Trump’s lawyers are arguing that because his information was “likely seen by tens of millions of viewers”—in what’s known as secondary disclosure—and was covered widely in the press, Trump is entitled to “at least” $10 billion in statutory damages. Several courts have already rejected the idea that secondary disclosures count under this particular statute. If the courts opt for actual damages, Trump’s lawyers are also arguing that he has suffered at least $10 billion in financial harm. The president has said that if he wins, he will give all of the money to charity (although he hasn’t always been faithful to his promises to donate funds).

The suit is just the latest of Trump’s legal attacks on both private institutions and his own government. Since his election in 2024, the president has secured $16 million each from settlements with the media companies Paramount and ABC, and almost $60 million total from settlements with the American tech firms Meta, Alphabet, and X. Trump also filed complaints in 2023 and 2024 against another federal agency, the Department of Justice, and has reportedly demanded $230 million in compensation for its past investigations into him—but he did not officially sue. My colleague Quinta Jurecic called it a form of extortion.

Theoretically, an impartial court will adjudicate Trump’s IRS case. But the president ultimately controls both parties to the lawsuit. A judge would have to approve a settlement, but Bessent, who works a second job as acting commissioner of the IRS and who reports directly to the president, would oversee the payout. Keith E. Whittington, a professor at Yale Law School, told me that, under the broad theory of executive power that Trump has embraced in the past, he could potentially give direct instructions to either Bessent or the lawyers themselves. Courts may get “pretty nervous about a situation in which, arguably, you’ve got the same person on both sides of the case,” Whittington said. Trump himself has noted the potential conflict of interest: “I’m supposed to work out a settlement with myself,” he recently told reporters.

Trump’s destruction of presidential norms has been well documented at this point in his second term. But the IRS lawsuit represents something slightly different. Until now, there was no expectation that a president might “put the government in this situation, in which he is trying to extract money from the Treasury to serve his own private interest while he’s a sitting president,” Whittington explained. “One might characterize that as a question of norms, but I doubt it even occurred to anyone to think about whether or not this is an appropriate thing to do.”

What does it say about how Trump understands his role if he is willing to sue his own government to line his pockets? The job is meant to come with trade-offs: In exchange for power over the federal government, a president usually surrenders some ability to prioritize their personal interests—by divesting their holdings from private companies, for example (Trump has not done this, either). With the IRS lawsuit, Trump has discovered yet another way to leverage his office for his own gain. The question of whether he can sue his own agency is perhaps less important than whether he should.

Related:

- Trump to DOJ: Pay up.

- Why Meta is paying $25 million to settle a Trump lawsuit (From January 2025)

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- Read The Atlantic’s interview with Volodymyr Zelensky.

- Why MAGA wants you to think slavery wasn’t that bad, by Thomas Chatterton Williams

- Carrie Prejean Boller is not going quietly.

Today’s News

- Funding for the Department of Homeland Security is set to expire tomorrow morning without a deal, which would force many agencies to operate through a shutdown. Immigration enforcement would continue, but airport security, disaster response, and other DHS functions could face strain if the shutdown persists.

- Two senior aides to Robert F. Kennedy Jr. are set to leave the Department of Health and Human Services as part of a broader leadership shake-up.

- A federal judge ordered the Trump administration yesterday to provide immigrant detainees near Minneapolis with adequate access to lawyers, saying that the government had “failed to plan for the constitutional rights” of the detainees during the enforcement surge.

Dispatches

- The Books Briefing: A cherished grudge might make it into a novel—but the best writers avoid creating books that feel one-sided, Boris Kachka writes.

- The Weekly Planet: Slashing funding for Arctic climate science will limit how clearly the United States can understand the region, Brett Simpson writes.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

Evening Read

Rod Dreher Thinks the Enlightenment Was a Mistake

By Robert F. Worth

On an April evening last year, Rod Dreher sat in the front row of an auditorium at the Heritage Foundation, in Washington, D.C., giddy with pride and happiness. He was there for the screening of a new documentary series based on one of his books, Live Not by Lies, about Christian dissidents from the former Soviet bloc—but first, a special guest was making his way toward the stage. J. D. Vance arrived at the podium to a roar of applause and told the crowd that he would not be the vice president of the United States if not for his friend Rod …

Unlike many in the crowd, Dreher, then 58, was not a staunch Donald Trump supporter; he had long criticized the president and came around only at the beginning of his second term, after concluding that Trump’s crude energy was needed to defeat progressive ideas. But Dreher has been giving voice to the yearnings and frustrations of religious conservatives for many years—as a magazine blogger with more than 1 million pageviews a month, an author of best-selling books, and a deliriously verbose writer on Substack. In January he joined The Free Press as a regular contributor. More than anyone else I know of, Dreher offers a full-fledged portrait of the cultural despair that haunts our era, a despair that has helped pave a road toward tyranny.

More From The Atlantic

- Putin didn’t know how good he had it.

- Galaxy Brain: Is AI ruining music?

- First jobs matter more than we think.

- Alexandra Petri: What fabulous timing for Gallup to stop tracking presidential approval!

Culture Break

Think about love. Many daters have a list of traits they’re looking for in a partner—but they can be perfectly happy with someone who has few of them, Olga Khazan writes.

Read. Brooke Nevils’s memoir is also a reckoning with many misconceptions about #MeToo narratives, Hillary Kelly writes.

Rafaela Jinich contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.