This article was featured in the One Story to Read Today newsletter. Sign up for it here.

Gregory Bovino, the man who became the face of Donald Trump’s Minneapolis crackdown, lost his job as the Border Patrol’s “commander at large” after agents he oversaw shot and killed Alex Pretti. Bovino also reportedly lost his X account, a development that may seem trivial until you remember: Bovino loves to post.

In the two days after Pretti died, Bovino relentlessly trolled Democrats who condemned the shooting—and defended Border Patrol agents as the real victims. When Representative Eric Swalwell wrote on X that ICE officers should walk off the job to protest the killing, Bovino replied: “I was thinking the same for you.” At about 1 a.m. last Monday, Bovino replied to a user who said he would “never pay for a beer again” after mocking Swalwell: “Lol!! 🍺 🍻 🍺 🍻 🍺 🍻.”

Getting silenced on X is, and I realize how absurd it sounds, the worst professional fate a Trump official can face. It signals that Bovino is no longer a player in an administration that has, from top to bottom, merged a social-media-first worldview with authoritarian tendencies. I like to call it the clicktatorship. Political appointees in the clicktatorship are not just using online platforms as a mode of communication. Their judgment and decision making are hyper-responsive to what’s happening on the far-right internet. They view everything as content.

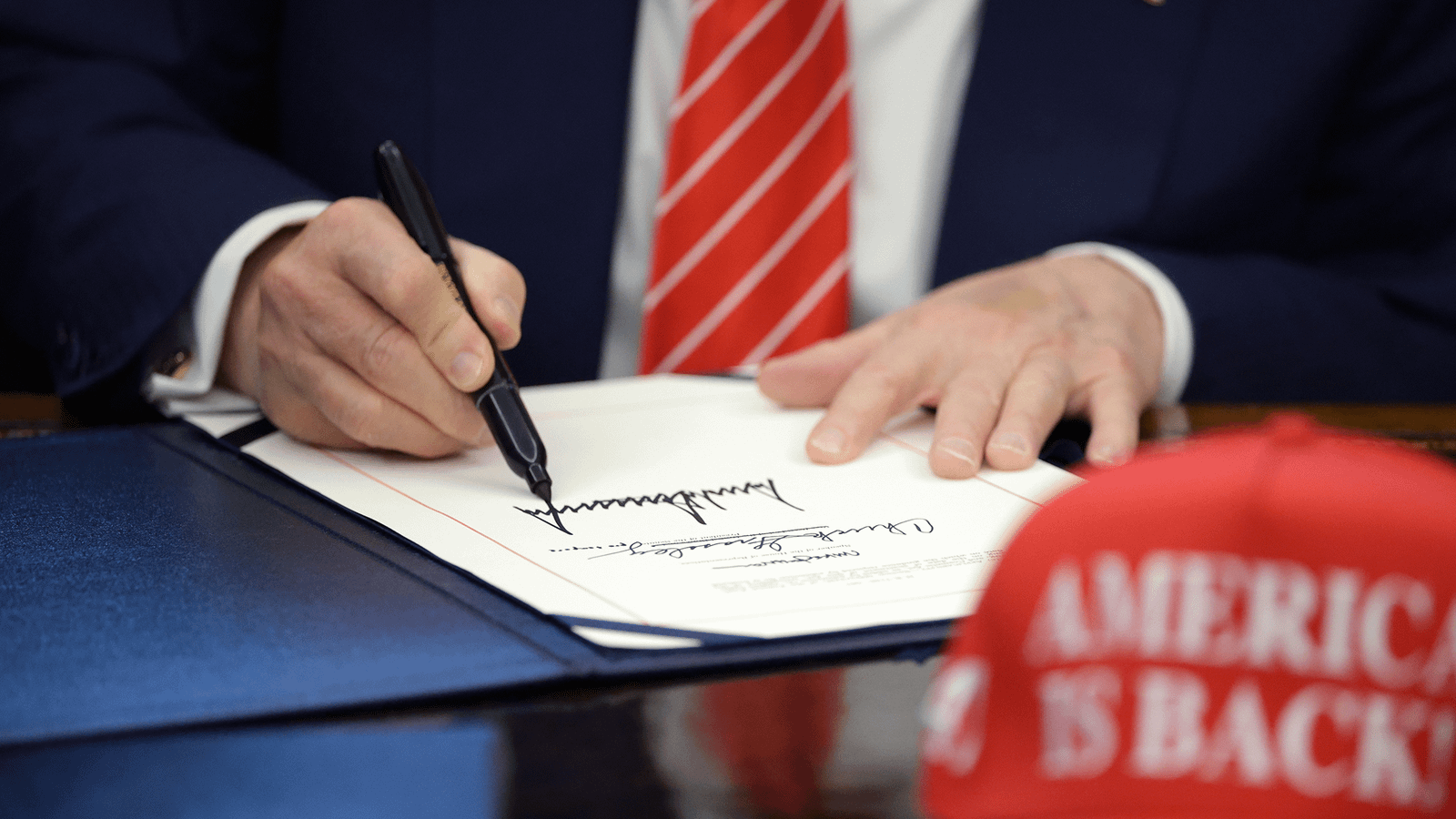

No one better exemplifies the clicktatorship than the president himself. Trump routinely makes policy announcements via social media. Consider when, in August, he attempted to fire the Federal Reserve Board member Lisa Cook on Truth Social. When a government lawyer was questioned by the Supreme Court on the lack of an appeals option for Cook, he suggested that Cook could simply have made her case on Truth Social. In the clicktatorship, due process is reduced to the right to post.

You can see it everywhere. The administration’s official social-media feeds pump out far-right xenophobic memes and celebrate deportations with ASMR videos of undocumented immigrants in shackles. Just days before the killing of Pretti, the White House posted an image of a woman who was arrested after a protest at a church in Minnesota. It had been edited, presumably using generative AI, to show the arrestee as weeping uncontrollably. The effect is to reinforce an impression of dominance and control. Truth matters less than attention. Reporters who pointed out the manipulation were mocked by a White House spokesperson, who posted: “uM, eXCuSe mE??? iS tHAt DiGiTAlLy AlTeReD?!?!?!?!?!” (“The success of the White House’s social media pages speak for itself,” Abigail Jackson, a White House spokesperson, told me in an email. “Through engaging posts and banger memes, we are successfully communicating the President’s extremely popular agenda.”)

[Read: The gleeful cruelty of the White House X account]

Aspects of the clicktatorship existed during Trump’s first term, when the president used Twitter as a bully pulpit. But it has ratcheted up to new levels in his second go-round. His appointees are more likely to be keyboard warriors. They are obsessed with spectacle, and every government decision presents a potential opportunity to own the libs. Our government lost 10,000 STEM Ph.D.s last year, but seemingly has more posters than ever.

Consider Dan Bongino, who jumped from hosting a podcast to becoming deputy director of the FBI. (Bongino recently stepped down and returned to podcasting.) Or Harmeet Dhillon, who was a paid X influencer on top of her day job as a lawyer before becoming the head of civil rights at the Department of Justice. She continues to post up to a hundred times a day, between her personal and professional X accounts. “I’ve been stuck at the same level of followers on this account pretty much since I started my government job,” she wrote on X last month. What, am I chopped liver over here? What kind of content do my folks want to see more of to like and share?” And after the Venezuela raid in early January, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth was photographed at a makeshift command center in Mar-a-Lago. Behind him was a screen displaying X posts.

[Read: Everything reacting to everything, all at once]

Poster brain and authoritarianism reinforce each other: They thrive on conspiracy theories, lack all restraint, and jump to extreme solutions. Trump officials pointed to claims about welfare fraud from the social-media influencer Nick Shirley to justify cutting off billions in aid to five Democrat-led states. And Trump-administration officials pointed to Shirley’s viral video in attempting to justify a crackdown in Minnesota that has now resulted in the death of two American citizens. Meanwhile, government budget proposals and strategy documents now read like Truth Social posts, replete with online tropes. The White House website now alleges that President Obama hosted terrorists, speculates that Hunter Biden had cocaine in the White House, and says that “it was the Democrats who staged the real insurrection” on January 6, 2021.

Social media and authoritarian regimes have one other negative tendency in common: They feed information bubbles. Online, people select into circles of those they already agree with. In nondemocratic regimes, senior officials wall themselves off from reality because their underlings are afraid to deliver bad news. In both cases, the bubbles encourage radical actions rather than compromise—doubling down rather than moderation.

But the thing about bubbles is that sooner or later they burst. The Trump administration maintained a unified front after the killing of Renee Good, arguing that agents were acting in self-defense, even when video evidence complicated that version of events. Many members of the administration attempted to follow the same playbook after federal officials killed Pretti. But the fiction has not held up. The people who put their bodies on the line to record what was happening in Minneapolis revealed a valuable truth. The same tool that makes clicktatorship possible—the smartphone—can also be used against it.