Nearly as old as Ahab (one more birthday and I’ll be 58: his age), I drive south from Boston on a recent Saturday morning. Through a raging drabness of Massachusetts wintertime, I drive and drive: leaky light without a source; seething, decaying snow.

I’m on a mission here. A collision with immensity awaits: the 2026 Moby-Dick Marathon at the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Programming, scholarship, and—the event’s steadily droning core—a 25-hour cover-to-cover reading of the great book itself. Hundreds of volunteer readers, in five-minute increments, from noon on Saturday to 1 p.m. on Sunday. A test of my fortitude as a listener, of my ability to keep my behind in a seat.

But I am faint. Succor is required. I pull over at the Bridgewater Service Plaza because sometimes what you need is to quietly conform yourself to the will of God, and sometimes what you need is a cup of stinking black coffee and a Dunkin’ glazed doughnut.

Into snowy New Bedford, into the Whaling Museum, into the room where they keep the Lagoda, the museum’s half-scale model of a whaling bark. A room with a ship in it, in other words. Two stories high (to accommodate the ship’s masts) and stuffed, draped, festooned with humanity: sitters, knitters, nesters, kneelers, sprawlers, leaners, drifters like me, stashed in every alcove and stretched along every railing and baseboard. At noon on the nose, the Massachusetts poet laureate, Regie Gibson, steps up to the lectern: “Call me … Ishmael.” The whoop, the sound of exulting Moby-Dick nuts, goes raggedly around the galleries and hallways of the museum. The tale begins, of course, in New Bedford, where Ishmael arrives “on a Saturday night in December” in search of a whaling voyage. We have embarked.

Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville, published in 1851. Let’s consider it. Is there another book at once so good and so bad, so thrilling and so boring, so authentic to the currents of the soul and so hideously contrived, so stunningly patrolled by dreamlike visions and so crushed by its own intellectual baggage?

There’s no denying the power, the pull, of its mighty twin symbols: burning-eyed indeflectible Ahab, captain of the Pequod, emblem of every human obsession, of the violence of the mind; and his quarry, the white whale, the lump of metaphysical mystique known as Moby Dick. Psychic facts, both of them. But what a welter of chaos they must rise through to reach us—what sub–Thomas Carlyle thunderings, what sub–Sir Thomas Browne conceits and curlicues, what sub-Shakespearean rants. Shakespeare especially: a terrible influence on Melville! All the interior monologues in Moby-Dick, and almost anything that comes out of the mouth of Ahab—all those reams of hoarse Elizabethan bluster—you can blame on Melville’s 1849 devouring of a new seven-volume edition of Shakespeare’s plays, in large print (he had weak eyes). Enthusiastic American, as he began writing Moby-Dick, he was wildly cranked on the Bard. But wait, hist, soft, listen—now we’re on Chapter 7, and a reader speaks out a perfect line of Shakespearean blank verse: “Faith, like a jackal, feeds among the tombs.” Beautiful. I kiss my hand to you, Herman.

Melville would have enjoyed the New Bedford Whaling Museum. Like him, it is given to the grand gesture: whale skeletons suspended from the ceiling, floating above us like hierarchs at a superior level of being; the aforementioned room with a ship in it; and, right by the table where I buy my endless sustaining blueberry muffins and meat pies and cups of tea, a 600-pound life-size model in fiberglass of a blue whale’s heart, its ventricles large enough for a man to crawl into.

The readers: They are everyone. They have every quality. They are stammering, assured, dubious, virtuosic, inaudible, room-shaking, thick-voiced, thin-voiced, professional, innocent, mesmerizing, devoid of presence. It’s an American pageant, purely democratic, intensely moving. Reader by reader, the thread of meaning, the pulse, comes and goes. Some of them seem to seize us by the very roots of our comprehension; others might as well be reading from the Terms and Conditions of Use for Spotify. The prose of Moby-Dick is dense; it can be unwieldy—Melville’s mouthfuls are too large for our 21st-century mandibles. Some words that people have trouble with: idolator, remonstrances, vicissitudes, magnanimity, portentousness. Also (this one surprises me): leviathan.

With merciful swiftness, it is revealed that I cannot, simply cannot, listen to a succession of persons read from Moby-Dick for 25 hours. It’s an impossibility for me. I’m a modern man with all of the modern vices: inattention, solipsism, wooziness, dopamine addiction, twitching legs, low blood sugar, a persistent interest in going to the bathroom. So I phase in and out of the Marathon. I wander the museum; I wander the night streets of New Bedford, with their hostile glints of ice. At 7:02 p.m., I’m in the Pour Farm Tavern on Purchase Street, brooding over a double Jameson. Out of the jukebox, loaded with 1970s baggage but still moving, in 2026, with a slinking, predatory roll, comes Ted Nugent’s “Stranglehold.” The maniac Nugent, essential American, once a hard-rock warlock, now a vaunting Trumpist. Listen to the song: “Road I cruise is a bitch nowww, BAY-BEH! / You know you can’t turn me ’round / And if a house gets in my way, BAY-BEH! / You know I’ll burn it do-own.” Wow. How fucking Ahab is that?

Coming and going as I am, nevertheless, in my blue-whale heart, I remain attached to the collective, to the shared journey, the shared imagining, all of us with our copies of the book, all of us enmeshed in the great and groaning text. At 4:15 a.m. in the museum’s main auditorium, there’s a long-haul-flight vibe, people looking pale and rumpled as we steer toward Chapter 87, one of the most limpidly head-expanding chapters of the book: “The Grand Armada.”

Somewhere around Java, the Pequod hunts its way into an entire shoal of sperm whales: Its boats are lowered, and whereas at the edge of the shoal, the harpooneers set about their bloody and ocean-churning business, Ishmael’s boat finds itself in the supernaturally serene center. Peaceable whales approach; “like household dogs they came snuffling round us.” And in the transparent depths, a vision is disclosed: nursing mother whales.

As human infants while suckling will calmly and fixedly gaze away from the breast, as if leading two different lives at the time; and while yet drawing mortal nourishment, be still spiritually feasting upon some unearthly reminiscence;—even so did the young of these whales seem looking up towards us, but not at us, as if we were but a bit of Gulfweed in their new-born sight. Floating on their sides, the mothers also seemed quietly eyeing us.

Incredible prose, somewhere between journalism and science fiction. But a few paragraphs later, Melville falls into his old weakness, his old foible—he starts symbolizing. The violence at the rim of the shoal, the stillness at the center … He can’t help himself. He must go Sir Thomas Browne on our asses: “Even so, amid the tornadoed Atlantic of my being, do I myself still for ever centrally disport in mute calm; and while ponderous planets of unwaning woe revolve round me, deep down and deep inland there I still bathe me in eternal mildness of joy.”

Is it a weakness, though? Maybe not. Maybe this nonstop back-and-forth, this spiritual reverb, this throb-throb oscillation between the actual and the symbolic, the objective and the imagined, is the heartbeat of Moby-Dick. Are things ever only themselves, or do they always attach to, refer to, other realities? Must all phenomena have meanings upon meanings? Can a whale ever be just a whale? My mind loops out. It’s 5 a.m. What if existence itself (a line from my notes) is a pun on existence? That’s pretty bloody Melvillean, dude. The man sitting in front of me—rugged, with a fine Rockwell Kent profile—tips forward and begins to emit gentle, bleating snores.

With the dawn—streaky and watery over New Bedford—everything accelerates. Now we’re in the final stretch. Now we’re closing in. At 9:30, in the museum’s research library, a group of Melville scholars holds a packed and slightly giddy informal symposium. A young man, confiding to us that this is his first time reading the book, and apologizing for the basic-ness of his question, asks, “Is Melville using Ishmael to, like, satirize the whole white-male epic of obsession and violence?” Beat. Hanging symposial silence—until one of the scholars, as in the Philip Larkin poem, pronounces an enormous “Yes!” and the room erupts into applause.

The final readings are happening upstairs, in the Harbor View Gallery, with livestreams to all parts of the museum. I’m watching in the auditorium, the doors are open to the main hall, and there’s a slight lag in the streaming between the two spaces. So on every phrase you get an echo: “There she blows!” (There she blows …) Talk about Melvillean reverb. Another line of pure Shakespearean verse drifts up: “Great hearts sometimes condense to one deep pang.” (Deep pang …)

And who’s this guy reading the last chapter to us, Reader 277? He’s got to be an actor, a TV guy of some sort: He has an actor’s expressive and sympathetic handsomeness, soap-operatic facial symmetry, no bad angles. His name is Steven Weber (of Wings and Chicago Med, I later discover), he takes a deep breath, and then, my God, he tears the roof off the Moby-Dick Marathon. What a performance. The last battle with the white whale, the destruction (spoiler!) of the Pequod. Weber’s Ahab is all Ahab; his Starbuck is perfectly impassioned. “Moby Dick seeks thee not. It is thou, thou, that madly seekest him!” We are agog. Afterward, briefly interviewed by the museum’s president, Amanda McMullen, Weber is almost overcome. “I’m so moved by this,” he manages. “This book, boy …”

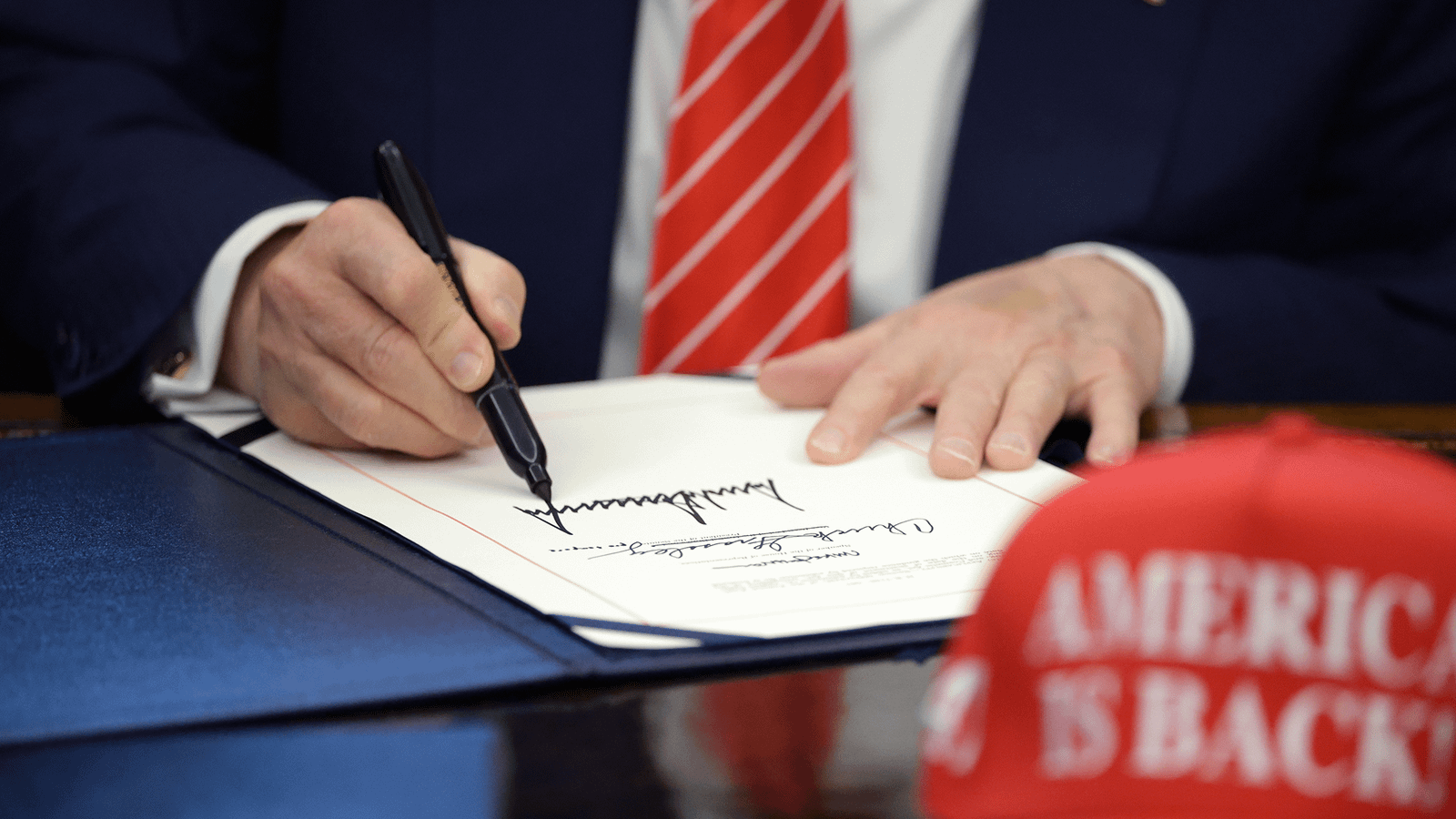

According to the reading’s organizers, more than 3,000 people attended this year’s Moby-Dick Marathon. Prediction: Next year, if the Whaling Museum can handle it, it’ll be 5,000. I don’t want to label this event a node of resistance, but … it kind of is. It’s a radical act. An all-analog mass redreaming of a book. And not just any book—a flawed American gospel. With Moby-Dick itself, I may have my little fancy-pants peeves, but let’s face it: Ahab is Donald Trump, and Ahab is me, and I am you, and Ted Nugent is the Pequod, and the whale is the whale, and the voyage is America. These resonances ring out; they ring out from New Bedford and keep going, traveling west until they roll down the hills of California and sink hissing into the sea.